Kathy, Blanca, Idalia, Aminta, Chon, and I piled into the car this morning around 8:30am. We were headed north to the department of Morazán, near Honduras, to see the massacre site at El Mozote, and Perquin, a guerilla stronghold during the Civil War. This was my second trip to both places. The first time I went was almost exactly 5 months ago in September of 2009 with the Westminster delegation. We arrived at El Mozote around 11:00am. The following is a description of the events at El Mozote. It comes from several sources, including information at the site and testimony by Rufina Amaya. I want to forewarn you that the story is graphic and disturbing. I will not gloss over the details.

The Massacre at El Mozote

The El Mozote Massacre took place in the village of El Mozote, in Morazán, El Salvador, on December 11, 1981, when Salvadoran armed forces trained by the United States military killed at least 1000 civilians in an anti-guerrilla campaign. It is reputed to be one of the worst such atrocities in modern Latin America history.

It began on the afternoon of December 10, 1981, when units of the Salvadoran army’s Atlacatl Battalion arrived at the remote village of El Mozote. The Atlacatl was a “Rapid Deployment Infantry Battalion” specially trained for counter-insurgency warfare. It was the first unit of its kind in the Salvadoran armed forces and was trained by United States military advisors. Its mission, Operación Rescate, was to eliminate the rebel presence in a small region of northern Morazán where the FMLN (guerillas) had a camp and a training center. The commander of the Battalion was Lieutenant Colonel Coronel Domingo Monterrosa Barrios, who was from Berlín.

In the afternoon of December 10th the five companies of Atlacatl Battalion arrived in El Mozote. Upon arrival, the soldiers found not only the residents of the village but also campesinos (rural people) who had sought refuge from the surrounding area. The campesinos had gone to El Mozote thinking it would be a safe place. The soldiers ordered everyone out of their houses and into the square. They made them lie face down, searched them, and questioned them about the guerrillas. They then ordered the villagers to lock themselves in their houses until the next day, warning that anyone coming out would be killed. The soldiers remained in the village during the night.

Early the next morning, on December 11th, the soldiers reassembled the entire village in the square. They separated the men from the women and children and locked them all in separate groups in the church, the convent, and various houses. At 8:00am the executions began.

Throughout the morning, they proceeded to interrogate, torture, and execute the men and adolescent boys in several locations. Around noon, they began taking the women and older girls in groups, separating them from their children and machine-gunning them after raping them. Girls as young as 9 were raped and tortured, under the pretext of them being supportive of the guerillas. Finally, they killed the children. A group of children that had been locked in the church and its convent were shot through the windows. After killing the entire population, the soldiers set fire to the buildings. Over 1000 people perished.

The massacre at El Mozote was part of a military strategy of genocide against the Salvadoran people. The government and army exterminated massive numbers of innocent campesinos in the war zones. The thought was to “take away the water from the fish”. As a result, many massacres of hundreds of rural families were carried out in various places in the country. The operations were known as “Land Clearing Operations”.

The guerrillas' clandestine radio station began broadcasting reports of a massacre of civilians in the area. On December 31, the FMLN issued “a call to the International Red Cross, the OAS Human Rights Commission, and the international press to verify the genocide of more than 900 Salvadorans” in and around El Mozote. Reporters started pushing for evidence.

Officials from the US embassy in San Salvador played down the reports and said they were unwilling to visit the site because of safety concerns. As news of the massacre slowly emerged, the Reagan administration in the United States attempted to dismiss it as FMLN (guerilla) propaganda because it had the potential to seriously embarrass the United States government because of its reflection of the human rights abuses of the Salvadoran government, which the US was supporting with large amounts of military aid.

It wasn’t until 1992, the year the Peace Accords were signed, that a team of forensic anthropologists were allowed to examine the convent in El Mozote. 136 children were found in that area. They determined that twenty-four shooters killed the children, using M-16 rifles and bullets manufactured in the US. The forensic experts concluded that it was a mass execution, and not the burial ground the Salvadoran government claimed it to be.

Rufina Amaya’s story

Rufina Amaya was the only survivor of the massacre. When it came time to execute the women, she stood last in line because she wouldn’t let go of her children. After they were taken from her and the men weren’t watching, she hid nearby, praying the whole time for God to protect her. She stayed there a long time until she had the courage to crawl many miles to safety. No words or pictures could possibly describe how she felt that day: Listening to the screams of her husband being tortured and dying, having her children ripped from her arms and ruthlessly slaughtered. On December 11, 1981 she lost her husband and four children, aged 9 years, 5 years, 2 years, and 18 months.

The memorial at El Mozote

They have not died, they are with us, with you, and with all humanity

This plaque bears the names of Rufina's husband and 4 children who died

Rufina Amaya's grave. She died March 6, 2007

The names of everyone who died in the massacre

The wall in the children's garden. Below are brown plaques that bear the names of all the children that died here

In this place they found in 1992 the remains of 146 people, 140 that were under 12 years old. All that were found are now buried in this monument

Beautiful roses in the children's garden

Names of children that died. Notice that the one at the top only says "Niña". Many children could not be identified

One of the names in the middle says "Ahijado de Florinda Díaz, 7 years old". Ahijado means godson. Others say "Hijo de" which means child of. They did not know the names of many children

One name at the bottom says, "Sobrino de Antonia Guevara". This means nephew of Antonia Guevara.

This plaque shows the ages of the youngest children. 3 days - 1 year old. One woman was also found who was in her 3rd trimester.

The Garden of the Innocent Children

Perquin

After leaving El Mozote we arrived at Perquin around noon. Perquin was under guerilla control during the Civil War and was known as part of the “red zone”. First we visited the Museum of Salvadoran Revolution. It contains documents, articles, pictures, and artifacts that belonged to the guerillas during the Civil War. The museum was founded by ex-combatants and attempts to recount the experiences of the guerillas. After looking through the inside of the museum we walked outside to see the remains of helicopters and airplanes. Probably the most famous is the wreckage of the helicopter of Colonel Domingo Monterrosa, who was the commander of the Battalion that massacred the people in El Mozote. We also saw a recreation of Radio Venceremos, which was a guerilla radio station during the war. Inside the recreated radio station is part of the device that was used to destroy Monterrosa’s helicopter.

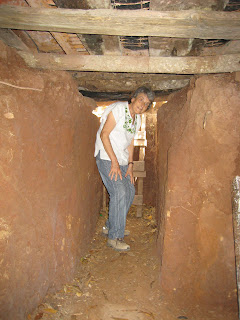

Next we went to Campamento Guerrillero, which was a former guerilla camp turned into an outside museum. It was fantastic! None of us had ever been there before. First we saw some of the weapons they used during the war including grenades, machine guns, and machetes. We walked on to see two recreated “tents” where the guerillas could stay dry when it rained. We went to the “kitchen” area, which they tried to hide so as not to be seen by the military. Over the kitchen was a roof of leaves and a pipe underground carried the smoke far from the kitchen. Next we came to a large hole in the ground that must have been at least 10 feet deep. It was made by a 500 pound bomb that was dropped but had not exploded. After that we saw the “hospital” area. The gurney was essentially large leaves wrapped around sticks that were being held up by pieces of wood. Our guide showed us the “ambulance”: a hammock. As Kathy said, “Could you imagine being operated on here?” I responded, “I think I’d rather die.” We walked on to a hole in the ground with a ladder coming out of it. It led down to an underground chamber and tunnel. This was a place the guerillas would have hidden if there were helicopters overhead.

Next we came to a series of three bridges. These were examples of bridges that the guerillas would have built while in the area. Typically, the guerillas would only stay in each area for 4 days. Then they would transport what they could and destroy the rest. The bridges were destroyed and rebuilt every time they moved. All were made of wood and rope over high ravines. After looking at a sign that said, “Only 3-4 people at once on the bridge” and “We’re not responsible if you fall” we crossed over the first bridge. The second bridge was made only of wood and wasn’t as long as the first. The final bridge swayed and dipped down quite a bit when we walked on it, but we all made it. We then walked by a sign that said, “Look, don’t touch”. Lying on the ground was a land mine that had never exploded. It has been sitting there for many years. The reason we couldn’t touch it was that it was technically still live. Now would it actually have exploded? I’m not sure. But I didn’t want to find out. After that we saw a bomb that was partially embedded in a tree. And with that we had reached the end of the tour.

At the Museum of the Revolution in Perquin. It reads, "Faceless Repression, Naked Innocence"

Remains of helicopters and airplanes

Firearms used by the guerillas

Radio Venceremos

A large hole created by a 500 pound bomb that was dropped. This picture doesn't do justice to how big the hole was

The sign reads, "Hole from a 500 pound bomb. Made in the United States"

Campamento Guerrillero in Perquin: firearms used by the guerillas

"Tent" used by the guerillas to stay dry when it rained

The "kitchen" area

This is where a bomb was dropped that did not explode. The hole is at least 10 feet deep

Our guide showing us the "hospital". Note the hammock "ambulance" in the background

Going into an underground tunnel used by the guerillas

Aminta going into the tunnel

First look inside the tunnel. It was made almost two decades ago

The way out is over there

Chon coming into the tunnel

An odd picture of me in the tunnel. It was dark with not much room

Coming out of the tunnel. The exit is pretty camouflaged

The first bridge

Posted to this bridge were two signs that read "Only 3-4 people at once on the bridge" and "We’re not responsible if you fall"

Making it across

The next bridge. Not so bad

Aminta on the third bridge. Notice how it dips down

Chon crossing the third bridge

I made it across pretty quickly. It reminded me of obstacle courses I used to do

You can do it, Kathy!!

"Look, don't touch"...

... because below is a land mine that hasn't detonated yet

Part of a bomb mangled in a tree

Lunch

We ate lunch today at Perkin Lenca, the same restaurant I visited 5 months ago. When you walked up the steps you could see for miles. It was beautiful. I also saw several flowers and some aloe vera. I ordered the same thing as before because I really liked it last time: Argentinean steak and chorizo with French fries. I bought some homemade pineapple jam and guava jam from the restaurant. I also got some delicious cookies that I tried last time I was there but didn’t buy. I was kicking myself for that and now I have two bags of them. Yum, yum, yum.

Then the most bizarre thing happened. A song was playing in the restaurant that I had been humming earlier in the car on the way to El Mozote. The song was, “It Must Have Been Love” which was released1987. I feel kind of embarrassed admitting that since I’m not a huge fan of love songs. There is no good reason for it to have popped into my head. I haven’t heard it for a long time and it has no connection with my previous El Salvador trips. There’s also no way I’d expect to hear a song in English from the 1980’s in El Salvador. I’m not quite sure how I’m supposed to interpret this or if it’s just something to help keep life interesting. It certainly shook me up a bit, but it was pretty cool at the same time.

We headed back to Berlín around 2:30 and arrived around 5:00pm. It had been a long day. I leave for school tomorrow at 7am. Wish me luck!!

Flowers at the restaurant in Perquin

Walking up to the restaurant

There is no way to peace, peace is the way. ~A. J. Muste.

5 comments:

Alisha, your blog posts are so interesting! It seems like you're having an amazing time!

Alisha,

So much to take in with your writings and pictures. Amazing and heartbroken stories you've written. Kevin

Wonderful post. The pictures and stories of the war are quite powerful. I'm glad you got to experience all of that. Sounds like quite a full day.

grasias me ayudaron a hacer mi tarea...

Indeed, not all who wander are lost..I am thankful that there are still people who care and remember what it is to be human.

Post a Comment